Risks tend to linger in obscure, unexpected places. So, even when your firm seemingly makes safe investments, things can go suddenly and terribly wrong if you don’t practice prudent risk management that considers all downside scenarios.

That’s one of the valuable lessons the latest U.S. bank failures taught financial institutions. The proximate cause of these catastrophes is a classic asset-liability mismatch story resulting from the sudden change in direction of interest rates over the past year.

This is a long-standing issue in banking that clearly deserves immediate attention, but the problems at SVB and Signature Bank were even more fundamental. These debacles can be directly linked to inadequate stress testing and scenario analysis approaches, which ultimately resulted in a huge loss of customer faith and a run to the exits.

It leads one to wonder about what the banks could have done differently, as well as what best practices other financial services firms should adopt to avoid a similar fate.

More Scenarios Needed

Despite best efforts, events can and will happen that can negatively impact financial investments or test customers’ faith. This could come from internal mismanagement that degrades the quality of finances, as in the case of SVB. Alternatively, an external shock might impact the ability of a bank to deliver critical products and services. Risk managers need to prepare for both types of shocks.

Economic scenarios allow us to run through simulations to understand how businesses could be impacted – and to then study potential solutions. Financial models can estimate the impact on profitably or losses should certain events occur, such as an increase in interest rates or an increase in energy prices. These results can help identify mitigation strategies, like hedging or selling portfolios, that companies can take proactively to reduce risk.

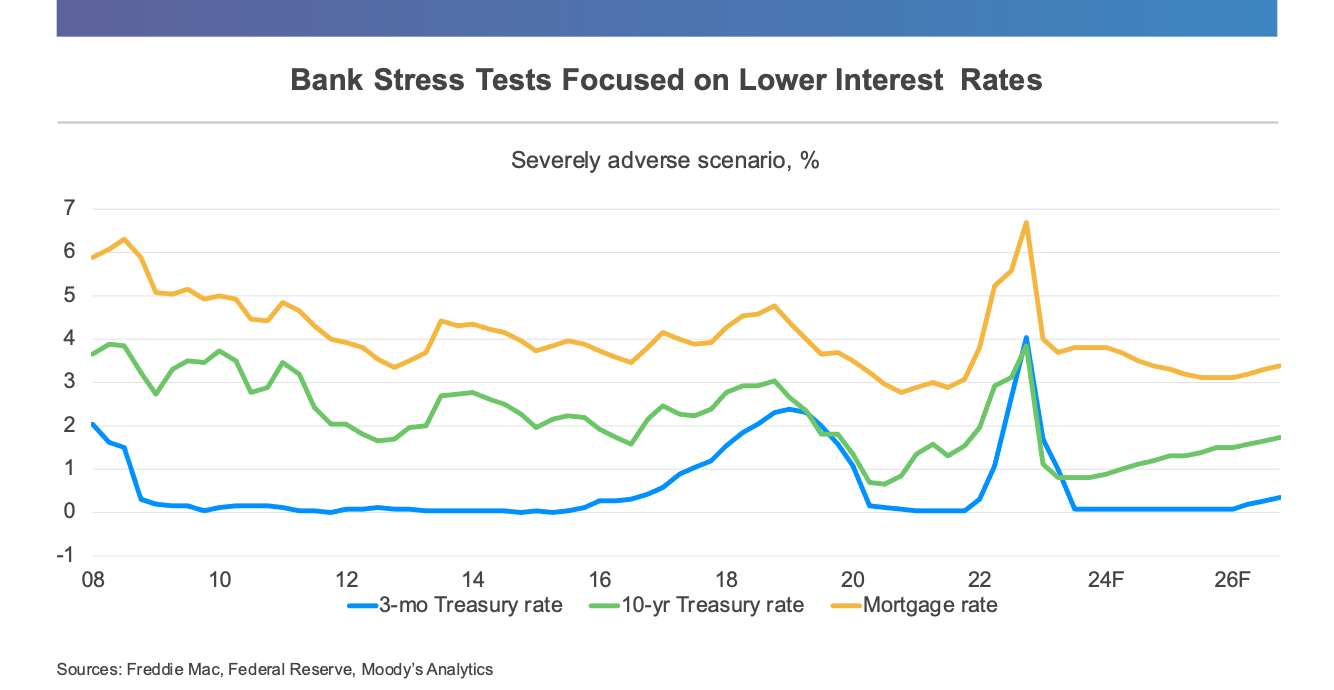

In the case of the recent bank failures, examining a wide array of stress-testing scenarios would have highlighted the weaknesses in asset and liability management sooner. Notably, many recent stress-testing exercises only considered scenarios where interest rates fall sharply (see chart, below).

Figure 1: The Limitations of Recent Stress Tests

While the approach depicted in Figure 1 may be reasonable for assessing the ability of a bank to withstand a large credit event, it does not account for the effect of a large interest rate shock. Recent experience highlights the need to consider a wider range of scenarios – especially those that seem to be unlikely given current conditions.

For example, high inflation and high interest rates were “inconceivable” a few years ago – but they aren’t any more. A key lesson learned is that stress testing that focuses on only a few scenarios from recent history can give a false sense of security.

Other Lessons Learned

The recent bank failures underscored the notion that risks tend to lurk in the places that aren’t examined. Investing in “safe” long-term U.S. Treasuries over the past few years may have sounded like the prudent thing for a bank to do. After all, these weren’t investments in risky subprime mortgages or esoteric derivatives that caused the collapse of banks during the Great Recession.

Indeed, backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S., these securities posed no credit risk. However, Treasuries still have interest rate risk. As rates rose, the market value of SVB’s portfolios fell.

Even these unexpected circumstances, though, didn’t necessarily have to result in the end of the line for SVB. The bank might have found a way to survive had depositors stayed put. It was only after customers lost faith and started to empty their accounts, en masse, that the bank collapsed. Transparency and additional scenario testing might have calmed depositors’ nerves earlier on, allowing the banks to find an alternative solution.

Cristian deRitis

To gain a better understanding of why this approach could have worked, just think back to the global financial crisis. During the height of the that fiasco, the stress testing instituted by the Federal Reserve went a long way to calm markets after the failures of Lehman Brothers and other institutions suggested that the entire financial system was about to implode. These stress tests shed light on the solvency of the banking system and were critical to restoring confidence as banks sought to rebuild their capital.

The lesson learned for financial institutions, both large and small, is that regular, rigorous stress testing is an essential part of prudent risk management. Debate around the appropriate level of regulatory testing and disclosures is reasonable, but the value of scenario analysis itself is clear.

More stress tests are needed, not fewer. Even if not required, banks and credit unions should consider voluntarily disclosing the results of their tests to boost customer confidence.

It’s important to remember that once trust eroded at SVB and Signature Bank, customers quickly fled. Risk professionals who want their employers to avoid a similar fate must use trust as a guiding principle when designing their scenarios and stress-testing exercises.

Trust Me

A loss of faith has been responsible for the downfall of many banks and businesses. Economic recessions ultimately come down to a collective loss of faith as well, making them difficult to predict.

Despite the central importance of trust to the success or failure of any enterprise, risk professionals often take it for granted. They may prefer to focus on the “numbers” for things they can measure, such as profitability or capitalization. Alternatively, they might assume that building trust in a company’s brand is the responsibility of the marketing department, rather than their own.

But establishing trust goes much deeper than marketing. Loss of confidence needs to figure prominently in institutions’ risk matrices. Building organizational awareness of the importance of trust is a good first step, but how should risk managers think about trust when building their models, designing their risk scenarios or setting their strategies?

For a bank, sound financial risk management is the primary factor in gaining customers’ trust. This justifies investments in technical experts, models, scenarios, and audits for measuring and managing these risks.

For an organization in a different industry, customer service may be the key driver of trust. If so, investments might focus on policies and procedures that support training, recruitment and technology to maintain a best-in-class status.

The stakes are high in both cases, as any slip-up could damage a firm’s reputation forever.

Parting Thoughts

Free market notions of private risk and reward sound reasonable in theory, but tend to fall apart in a crisis. Time and time again, we’ve seen that government will not simply look away when markets fail, given the negative externalities associated with an increase in mortgage foreclosures or a bank run.

Traditional gauges of financial risk are helpful, but they need to be augmented with a greater appreciation of both qualitative and tail risks. Once trust in an institution is lost, it’s nearly impossible to recover.

Well-designed simulations and scenarios can help managers appreciate the downside risk of threats, such as an interest rate hike or a cyberattack, and to then take proactive steps to reduce exposures while they still can. But this type of analysis requires creativity.

Risk professionals need to be open to an expanded set of potential risks, while letting go of preconceived notions of investments that are “safe” or “inconceivable” situations. No investment is truly risk-free. As the collapse of SVB reminded us, even ultra-safe US Treasury bonds carry their own set of risks that need to be managed.

Cristian deRitis is the Deputy Chief Economist at Moody's Analytics. As the head of model research and development, he specializes in the analysis of current and future economic conditions, consumer credit markets and housing. Before joining Moody's Analytics, he worked for Fannie Mae. In addition to his published research, Cristian is named on two U.S. patents for credit modeling techniques. He can be reached at cristian.deritis@moodys.com.

Topics: Modeling