Over the past 12 months, bank have faced a myriad of difficulties, ranging from data deficiencies to dwindling profits to rising default risk and falling interest rates. Complicating matters further, regulators require absolute compliance, and it should therefore come as no surprise that managers of credit risk units are seeking to improve the efficiency of their workflows.

To meet this goal, banks are increasingly turning to the Six Sigma methodology - an approach that is intended to help them prioritize their credit risks. Of course, banks must consider both the potential benefits and detriments of Six Sigma before making any workflow efficiency decisions.

Today, credit risk organizations within banks are under much pressure. Regulators require absolute compliance with the Basel regulation; clients want to receive favorable rate for loans; modeling departments need better data to fulfill their mission of attaining higher predictive power; and validators must manage a large and at times unpredictable stream of models that need to be verified to ensure that they have been developed according to strict policies and standards.

For the professionals and managers that work for these units (credit approval, modeling, validation or collections units), the regulatory requirements are often absolute: the supervisor must be satisfied; capital, provisions and ratios must be calculated in accordance with the applicable legal frameworks; and the validations must take place before stated deadlines - i.e., prior to annual validations and backtests of internally-modeled risk parameters.

In the big picture, what is sometimes underplayed is the cost of credit risk compliance. Budgets are under pressure, and questions are asked about how many employees should work in the credit risk units and how their effectiveness should be gauged. Compliance, of course, is not inexpensive, and, while regulatory pressure has increased, the profits of traditional banking practices - such as income based on the interest-rate spread - are now eroding.

While all of this applied just before the COVID-19 crisis, the pandemic and the ensuing lockdowns only exacerbated the situation. Indeed, as the crisis has unfolded, banks have faced more default risk (increased PD) from borrowers and rising risk costs.

Given these circumstances, the fact that an efficiency goal is back on banks' credit risk management agendas is unremarkable. Since compliance is non-negotiable, the question now is how can financial institutions adequately fulfill their obligations (toward clients, supervisors and society at large) under budget constraints?

Six Sigma Benefits

Let's consider, for example, a credit risk model development department that needs to redevelop IRB models for some portfolios of the bank while simultaneously adding IFRS 9 overlays for expected credit losses (ECL). The department manager has to deliver the same number of high-quality models while working with a smaller budget, but where can he or she start?

COVID-19, again, complicates matters. Today, the manager cannot just “manage by walking around,” checking if staff members are doing the right thing, because most of his or her employees are now working from home. He or she can touch base regularly with team leads and other staff, but this only gives an indirect and qualitative impression about modeling outputs.

Filling this gap is where Six Sigma can prove valuable, and it is consequently not a great surprise that it's experienced a bit of a renaissance. Typically, this approach consists of five steps: define, measure, analyze, improve and control - commonly known as DMAIC.

Six Sigma starts with the workflow that leads up to a deliverable - in our case, a redeveloped credit risk model. Along the way, it asks important questions about the voice of the customer (VoC) and the process execution of the workflow.

Customers can be external or internal: the model owners are typically seen, for instance, as clients of the model development department. The VoC captures the customer requirements - e.g., a model must be with the Basel Committee's IRB rules and must have a predictive power of at least 85% of the area under the curve (AUC). Sometimes, the VoC is applied to more measurable targets, known as critical-to-quality (CTC) outputs in Six Sigma language.

Six Sigma also helps a manager determine whether time is being spent on non-value added (NVA) “process steps” within the workflow that are not particularly relevant to the bank or its internal clients. While Six Sigma is ruthless about eliminating these NVAs, one should evaluate the DMAIC process with care, because some steps that are flagged as NVA are actually needed - e.g., to train or retrain staff.

Fitting Measurement with Tolerance

As per the Six Sigma methodology, measurements related to the time spent on steps in the workflow are assessed against their tolerance. Outcomes outside of the tolerance are called “defects.” Six Sigma helps mitigate the problem of defects by trying to reduce the standard deviation of the time spent on the steps in the workflow while eliminating NVA activities.

Data preparation is one example. While risk managers in a modeling department need to do some data preparation, their primary mission is to find patterns in the data - and to put these to good use by developing a highly predictive credit risk model.

Often, it turns out that the time spent on data preparation is widely different from one credit risk modeling project to another. In such cases, because of a high process variability, an overabundance of time and resources may be spent on data preparation.

Many techniques within Six Sigma are meant to measure and mitigate such inefficiencies. When successfully applied, it ensures that a firm's process outcomes almost never fall outside of its tolerances.

The name Six Sigma relates to a process that is of such high quality that it is almost always “right, the first time.” It's based on the premise that investments in making a process more robust (i.e., less subject to variation) tend to pay off in the eradication of rework.

Credit Risk Implications

For applications of Six Sigma within credit risk departments (including credit approval, collections and risk modeling/validation), typically two types of measurement exist: “follow the individual” or “follow the file.”

“Follow the individual” means that the staff is asked to register how they spend their time in blocks of, e.g., 30 hours. Statistics, under this approach, are only reported on an aggregated basis.

“Follow the file” requires risk managers to follow one file through the flowchart of, say, a collections or credit approval process. This is especially relevant if the VoC relates to throughput time - the distribution of the total time between the start of work and its release to a client - rather than efficiency - e.g., the number of hours used to produce one model output.

The results of the first Six Sigma measurement phase are often surprising, if not shocking. A “follow the individual” analysis, for instance, might produce the following initial insights for a credit risk modeling department: (1) an organization spends an inordinate amount of time on indirect activities, such as team meetings; (2) more time than expected is spent on data preparation; and (3) employees often use overtime to compensate for time lost on indirect activities.

Example: Model Development

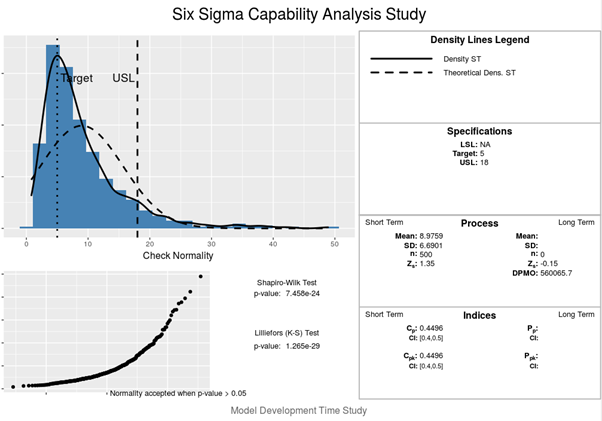

An example of a Six Sigma process capability study is illustrated below, using the “Six Sigma package with R.” In this case, the time spent on data preprocessing should not exceed 18 hours (i.e., the tolerance or upper specification limit), per project, for all model development projects (“follow the file”) considered. The department's manager in this example thinks that, on average, 5 hours per project is reasonable, since the data preprocessing is undertaken by a support unit.

For a sample of credit model development projects, the date/time stamps are collected so that, for each step in the process, an empirical distribution can be made for the time that is actually spent on these steps.

In the figure above, we see both the empirical distribution and the fitted normal distribution. We see also the target value (five hours) and the upper-specification limit, or USL (18 hours). In the bottom graph, the hypothesis for a normal distribution is rejected, so the normal distribution fit is not helpful in this particular case.

On the right-hand side of the graph, we see that the process capability (“Cpk”) is calculated as follows:

with x the measurements for this process step (in hours). The underlying idea is that the more standard deviations can be squeezed into the distance between the USL and the mean, the better (or “more capable,” in Six Sigma terms) the process. Within Six Sigma, this standard-deviations value is targeted at levels larger than 1.25.

Parting Thoughts

These days, capital optimization strategies around IRB seem to have leveled off, and the focus amid COVID-19 seems to be on improving workflow efficiency. Consequently, we've seen a renewed interest in Six Sigma in the financial services industry.

The mechanical premises of Six Sigma are controversial, because they support a strong division between “workers” and “management.” Indeed, it's important to remember that the roots of this approach trace all the way back to the Industrial Revolution, well before the time when the idea of worker empowerment gained traction.

There is nothing wrong with measurement processes that help banks make informed decisions about reengineering the credit risk workflow. But it's also true that the opinions of Six Sigma gurus and their colored belts should be taken with a grain of salt. Six Sigma principles can help credit risk units optimize their flow, but should not be seen as a comprehensive approach to management.

Dr. Marco Folpmers (FRM) is a partner for Financial Risk Management at Deloitte Netherlands and a professor of financial risk management at Tilburg University/TIAS.