Credit market observers are expecting a bull run to continue well into 2021. Volatility is seen as likely to persist as the pandemic continues to rage, and it may deepen if political divisions remain.

Credit spreads exploded last March amid the COVID-19 outbreak. Spreads subsequently tightened. Yields even on high-yield debt dropped to record lows.

High-yield bond issuance was estimated to top $400 billion in 2020 as issuers raced to refinance debt at record-low costs. The ICE BofA US High Yield Index Effective Yield was a historically low 4.52% and remained attractive to investors scrambling for returns.

“We think the market is ignoring all the COVID issues and looking right past that,” MUFG Capital Markets co-head of debt capital markets Jeffrey Knowles said in a December 4 media roundtable presentation. “Private equity, investors and even individuals have cash, so there's a lot of money chasing transactions.

Also optimistic, from a buy-side perspective, is Robert Tipp, chief investment strategist and head of global bonds at PGIM Fixed-Income. He said recently that with central banks accommodative and inflation muted, “there are macro opportunities, but even more so, sector and issuer-specific opportunities.” These include high-grade and high-yield bonds as well as emerging market sovereign debt. “There's room for spreads to compress in aggregate and within those credit sectors,” Tipp said.

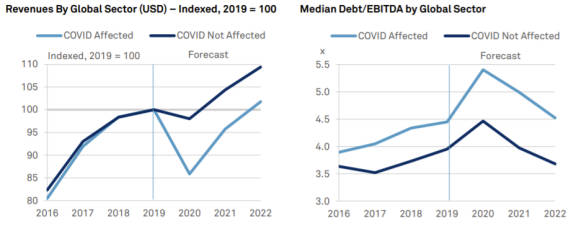

Overall Leverage

Still, there are credit quality concerns.

S&P Global's Global Credit Outlook 2021 report, published December 3, assumes the pandemic will come under control starting in the second quarter, and more broadly in the second half. Even so, it lists several potential credit challenges stemming from the severe economic damage, the dramatic expansion of private and public debt, and undermined business models on which complex debt structures reside.

One “very high” risk, to S&P, is fiscal and monetary stimulus pushing global leverage to 265% of global GDP, a concern currently mitigated by ample liquidity and the low cost of debt.

“Yet if debt grows faster and income recovers slower than expected, high debt would be harder to manage,” S&P says.

Crisis Aftermath

An analysis of corporate debt overhang by Federal Reserve Bank of New York economists concluded that residual economic effects could be more severe than those that followed the Great Recession. That earlier period was particularly hard on “firms with more significant needs for external funding.”

“Corporate sector indebtedness stood at record-high levels at the time of the outbreak in early 2020,” Kristian S. Blickle and JoÃo A. C. Santos wrote. “Based on data available for the first two quarters of 2020, we see that firms that entered the COVID-19 crisis with high levels of overhang experienced slower or even negative growth during the first half of 2020.

“Moreover, the economic shutdown that followed the spread of COVID-19 had a significantly negative effect on firms' cash flows. This is likely to have mechanically raised the debt overhang of firms in affected industries during the crisis.”

Another debt category, institutional leveraged lending, was the subject of a U.S. Government Accountability Office report in December. Noting that loans to highly indebted corporate borrowers surged over the last decade and invited comparisons to subprime mortgages circa 2007-'08, the GAO said: “After the COVID-19 shock in March 2020, loans suffered record downgrades and increased defaults, but the highest-rated CLO [collateralized loan obligation] securities remained resilient. Although regulators monitoring the effects of the pandemic remain cautious, as of September 2020, they had not found that leveraged lending presented significant threats to financial stability.”

A Difficult Winter

In a December Bank of America Global Fund Manager Survey, “fiscal policy drag” and “a credit event” ranked as the third- and fourth-biggest tail risks, behind COVID-19 and inflation.

Tom Joyce, global head of investment banking capital markets strategy at MUFG, said in an interview that most investment-grade, large-cap companies have done “a very good job pre-funding liquidity and working capital obligations.”

He noted that virus resurgence will likely be challenging, and he anticipates a difficult winter for the real economy. “Markets can still trade through that,” he said, gaining strength from “the remarkable vaccine progress.”

He added that many large-cap companies have strong liquidity, “virus-resilient business models,” and diversified revenue streams, in part due to rebounding Asia-Pacific economies.

The more than $17 trillion in negatively yielding securities globally puts U.S. investments in an attractive light. Joyce said that investors' bid for yield may have become excessive in the lowest rated sectors. He added that investors will “generally find more value” in the BB and BBB market segments as well as cyclicals such as industrials and financials that were beaten down in earlier virus waves.

Areas of Caution

Investment-grade credit may be safer over the next few months, Joyce said, but MUFG expects high-yield to outperform as the economy and public health begin to normalize. Although credit markets were bullish independent of the November election outcome, political and pandemic-related uncertainty could lead to significant volatility.

“That's why sizable fiscal stimulus from Washington is so important, to bridge the gap for the most vulnerable sectors in the economy,” Joyce said.

S&P forecasts the speculative-grade default rate rising to 9% in the U.S. and 8% in Europe by September 2021, compared to 6.3% and 4.3% last year, as highly leveraged companies in hard-hit industries such as retail, leisure and energy struggle. MUFG bankers believe investors' abundant capital will temper that impact.

Nevertheless, investors are taking some precautions - tightening prepayment baskets, seeking lower incremental indebtedness, and otherwise increasing control, said Art de PeÑa, head of loan syndicate and distribution at MUFG. They have not gone so far as to seek new structures and covenants.

“I think the dynamics are the same, but there's a shift in the level of each covenant structure,” de PeÑa said.

Drivers of Volatility

In the more challenging sectors and some middle-market transactions, and given the uncertainty ahead, he added, leverage, fixed-charge and other financial covenants are still required, and investors may seek earlier amortization.

Longer term, while abundant capital has recently been a lifeline for many borrowers, it may signal future more volatility. Tipp said that has been the pattern of past crises, pointing to Long-Term Capital Management in 1998. Demographics and slower growth are factors, but the main driver is ever-higher debt.

“Down the road, whether it's three, five or 10 years, when we get to the next crisis, you'll have even more debt and more volatility,” Tipp said.