European banks that must comply with the IFRS 9 financial reporting standard suffer today from a lack of supervisory guidance on how, exactly, they should go about weighting the scenarios they use to calculate expected credit losses (ECL).

Should they, for example, place more weight on a pessimistic ECL scenario if a crisis is projected to be on the horizon? In the case of exogenous shocks, like the COVID-19 pandemic, an argument can certainly be made for adjusting scenario weights for ECL.

But under all other circumstances (i.e., normal business cycles), the most logical approach is to update the values of the macro drivers regularly – preferably quarterly – while keeping the ECL scenario weights the same.

Before we dive further into the reasoning behind maintaining consistent scenario weighting (with the exception of exogenous shocks), we must first understand the way banks use scenarios today to calculate ECL in compliance with IFRS 9 – and the processes they employ to weight them.

A Three-Pronged Approach

When calculating ECL for IFRS 9, most banks use three scenarios: base, optimistic and pessimistic. A bank’s portfolio ECL is a probability-weighted average of the scenario ECLs. IFRS 9 describes this calculation as follows: “Expected credit losses are a probability-weighted estimate of credit losses […] over the expected life of the financial instrument.”

Macroeconomic information is used in each of the three scenarios. GDP growth, inflation rate and house prices are often used, but other macro drivers are possible as well. GDP growth is generally regarded as the most important driver.

In the base scenario, the expected growth paths for GDP and the other macro drivers are used, while appropriate adjustments are applied for the optimistic and pessimistic scenarios – e.g., projecting lower GDP growth (than for the base scenario) in the pessimistic scenario and higher GDP growth in the optimistic scenario.

The macro series have an impact on the projected risk drivers – probability of default (PD), loss-given default (LGD) and exposure-at-default (EAD). For example, in the pessimistic scenario, more defaults are expected than in the base and optimistic scenarios, and ECL will therefore be higher.

Marco Folpmers

Banks usually employ all three scenarios, resulting in the use of three probabilities that sum to one for the scenario weighting. The largest probability is usually attached to the base scenario, with smaller probabilities for the optimistic and pessimistic scenarios. A common weighting scheme is, for instance, 15%/70%/15% for the pessimistic, base and optimistic scenarios, respectively.

These weights can be adjusted to account for scenarios of different severities. A highly pessimistic scenario (say, GDP growth, minus 10%), for example, will receive a smaller weight than a moderately pessimistic scenario (GDP growth, minus 1%).

Three scenarios are typically needed to properly accommodate the non-linear impact that a change in macro drivers has on the risk parameters in a bank’s portfolios. This is also referred to as “the common approach” by the European Banking Authority in its 2021 IFRS 9 Monitoring Report.

A Simple Scenario-Weighting Rule

So far, this is all standard theory and practice. But it leads to an important question: should scenario weights for ECL be adjusted if one expects a recession? Under such circumstances, the pessimistic scenario would have a higher probability of realization, and one could then make a strong argument that the weights should be modified.

Surprisingly, the-standard setting bodies (e.g., the IASB, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, and central banks) have, to date, offered very little guidance on ECL scenario weighting at banks. Consequently, we have seen a divergence in approaches.

The EBA's 2021 IFRS 9 Monitoring Report confirmed this variability in scenario-weighting practices for ECL, explaining that while most banks increased the probability of the pessimistic scenario in response to the COVID-19 crisis, some actually decreased their pessimistic-scenario weights.

Changing the scenario weights for ECL during a typical business cycle can potentially lead to hypercorrections for the business cycle impact, ultimately resulting in exaggerated additions to/releases from ECL and unnecessary profit-or-loss volatility. Moreover, such revisions may also yield procyclicality, escalating the damage caused by a crisis. Increasing the weight of the pessimistic scenario in anticipation of a recession, for example, could lead to exaggerated provisioning, thereby constraining capital that would otherwise be available for lending.

To avoid unnecessary volatility in scenario weighting and to improve their ECL forecasts, banks should follow a simple rule: scenario weights should be kept stable under all normal business cycles, and should only be modified in the case of exogenous shocks.

ECL Provisioning: An Explainer

Before the logic behind this rule set is clarified, we must bear in mind that IFRS 9 provisioning is a departure from the “old” IAS 39 system, which was backwards looking. This was exactly the reason why IAS 39 needed replacement, since the provisioning for credit losses was seen as “too little too late”. Indeed, the IAS 39 approach not only reinforced the procyclicality of the banking sector but also exacerbated the global financial crisis of 2007-2009.

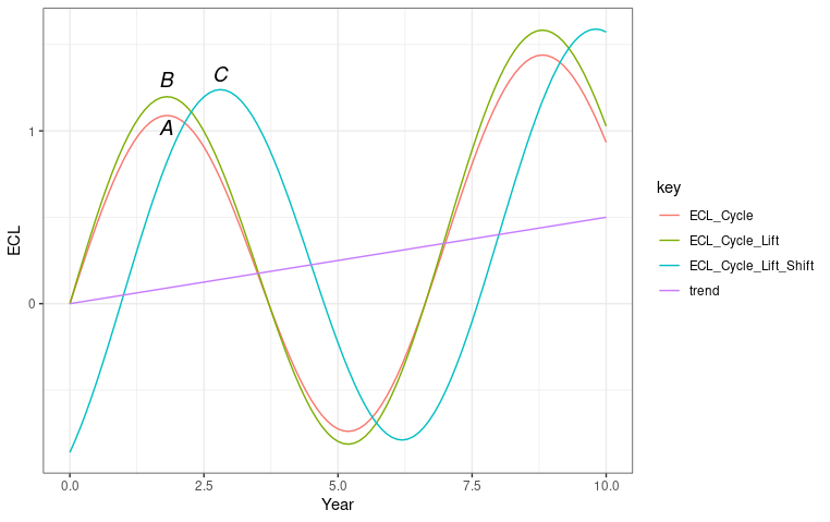

Keeping this in mind, let’s have a look at a stylized example of ECL-based provisioning for IFRS 9. In Figure 1, the additions to/releases from provisions are illustrated. The red curve depicts the build-up/release of ECL during a seven-year cycle, while the purple line shows an upward-sloping trend growth.

Figure 1: ECL-Based Provisioning – A Stylized Example

At point A, the additions to ECL are at a local maximum. At this point in time, provisions need to be built up for a decline that has not yet started but is considered to be “at the doorstep.” The forward-looking information is clearly indicating a macro downturn. Ideally, at this point in time, the bank’s profit is at its peak, and forward-looking provisioning is being maximized.

In our example, the values of the macro drivers are updated by the bank on a quarterly basis. Therefore, they must take a potential downturn into account.

If these series are correctly updated, there is no need to adjust the weights themselves. Increasing the weight of the pessimistic scenario, in particular, would lead to “hypercorrection” – i.e., a correction for a circumstance that doesn’t need any adjustment, because it has already been accounted for in the values of the macro drivers.

However, if a bank (erroneously, in my view) chooses to increase the weight of the pessimistic scenario with an eye on an upcoming recession, it can easily land at point B on the green curve. As long as the peak of the provisioning coincides with the high point of the business cycle, the situation would still not be procyclical. But it would be detrimental, since it could lead to unnecessary swings in ECL provisioning.

The Procyclicality Conundrum

It’s important to remember that our example is highly stylized. Peaks in ECL will, in practice, not always coincide with peaks of the business cycle. Since business cycles can be quite volatile, it is therefore possible that the peak in a bank’s ECL provisioning could lag behind, so that we end up at point C (see Figure 1) on the blue curve .

In our example, at point C, the bank is late in recognizing the upcoming crisis, and makes a peak addition to provisions while the downturn is already under way. In this case, the bank has also increased the weight of the pessimistic scenario (see point B on the green curve) and ends up in a situation where it has to set aside additional provisions at perhaps the worst possible moment.

If multiple banks were to act in this same manner, the collective exaggerated addition could exacerbate our mock crisis, since there would be less capital available for lending.

Stay Cool

The remedy to this situation is to remain calm. Don’t change the scenario weights just before or during downturns. Moreover, don't change the scenario weights at all throughout the business cycle. If they are timely and correctly updated, the values of the macro drivers will properly account for any changes in the cycle.

The only reason to revise the scenario weights is a breakdown of the cycle itself. If there’s an exogenous shock, such as COVID-19 or geopolitical turmoil, it makes sense to rethink the scenario weights. If a bank, for example, adopts the time series for the GDP growth from its central bank and perceives that a recent exogenous shock has not yet been accounted for in the data, this may lead to a correction through the scenario weights.

Even under extreme tail-risk scenarios, however, it is still important to figure out whether the scenario weights are in sync with the values of the macro drivers. If these are not aligned, one should consider a further correction of the scenario weights.

The most logical way to implement best practices for ECL scenario weighting is to document the rule set for the updating of the scenario weights, along with the procedures for updating the macro drivers themselves. This will be helpful for the ECL modelers, the model users, the accounting department and the auditors.

Dr. Marco Folpmers (FRM) is a partner for Financial Risk Management at Deloitte the Netherlands.

Topics: Default