Whether climate risk is actually a threat to financial stability has been a subject of ongoing debate. But a recent regulator-driven stress test has offered some clarity on this hot-button subject.

A few weeks ago, the European Central Bank released the findings of their top-down climate stress test. The empirical work backing the report was extremely detailed, thorough and innovative, as researchers applied arguably the best currently available data to capture the effects of climate change on corporate credit risk.

The results, in many ways, were stark.

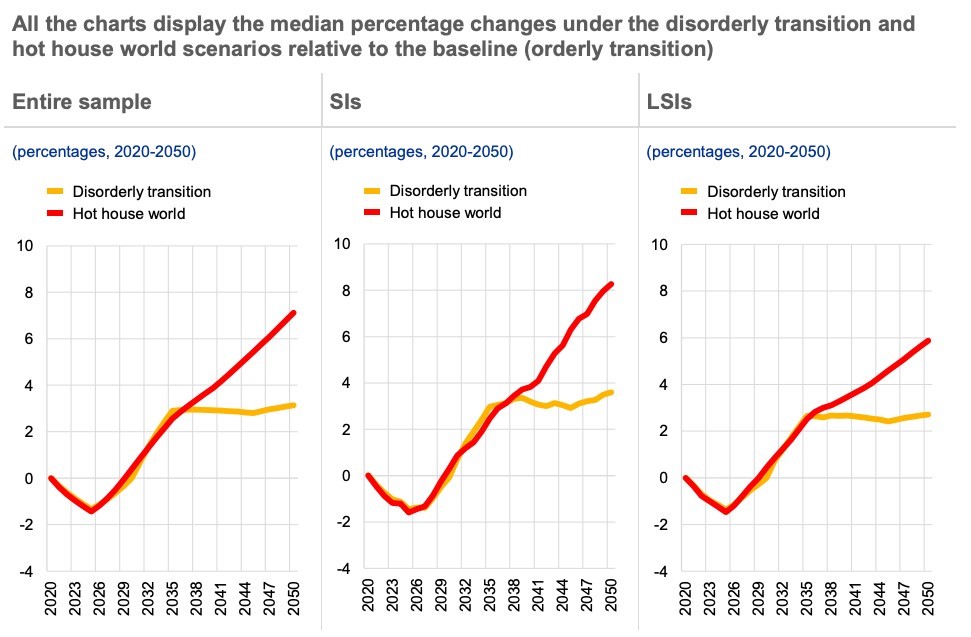

But through the critical credit risk channel, only a modest effect was identified. Relative to the ideal early response scenario, the dire hothouse world projections generated a 7% probability of default (PD) delta over the 30-year forecast horizon for the median portfolio (see Figure 1 below, as well as page 55 of the report) and a 30% PD delta for the more volatile tail portfolio (page 58).

Figure 1: Probabilities of Default - Percentage Changes Relative to the Baseline Scenario

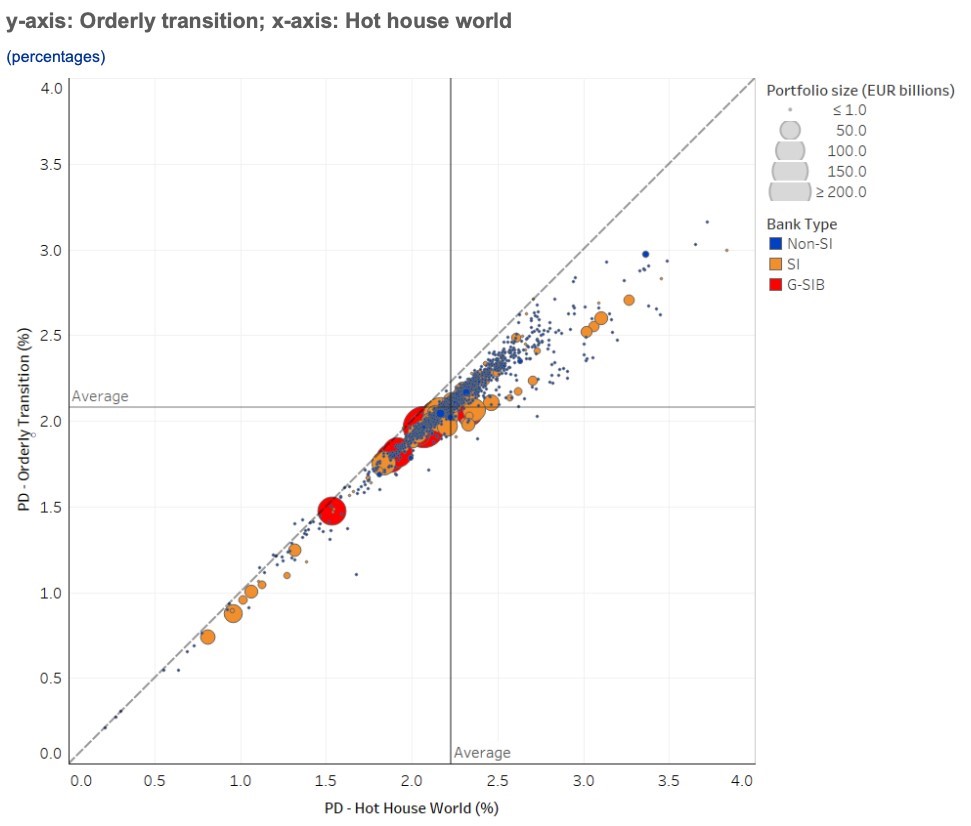

Given these figures, a baseline aggregate PD of 2.1% would translate to a hothouse PD of between 2.3% and 2.7% in 2050. The most heavily impacted individual bank in the ECB's sample (see Figure 2 below, and Chart 38 from the report) was predicted to have a 3% PD under the baseline orderly transition scenario and a 3.8% PD when the hothouse world projections are applied.

Figure 2: Probabilities of Default by 2050 - Orderly Transition vs. the Hothouse World

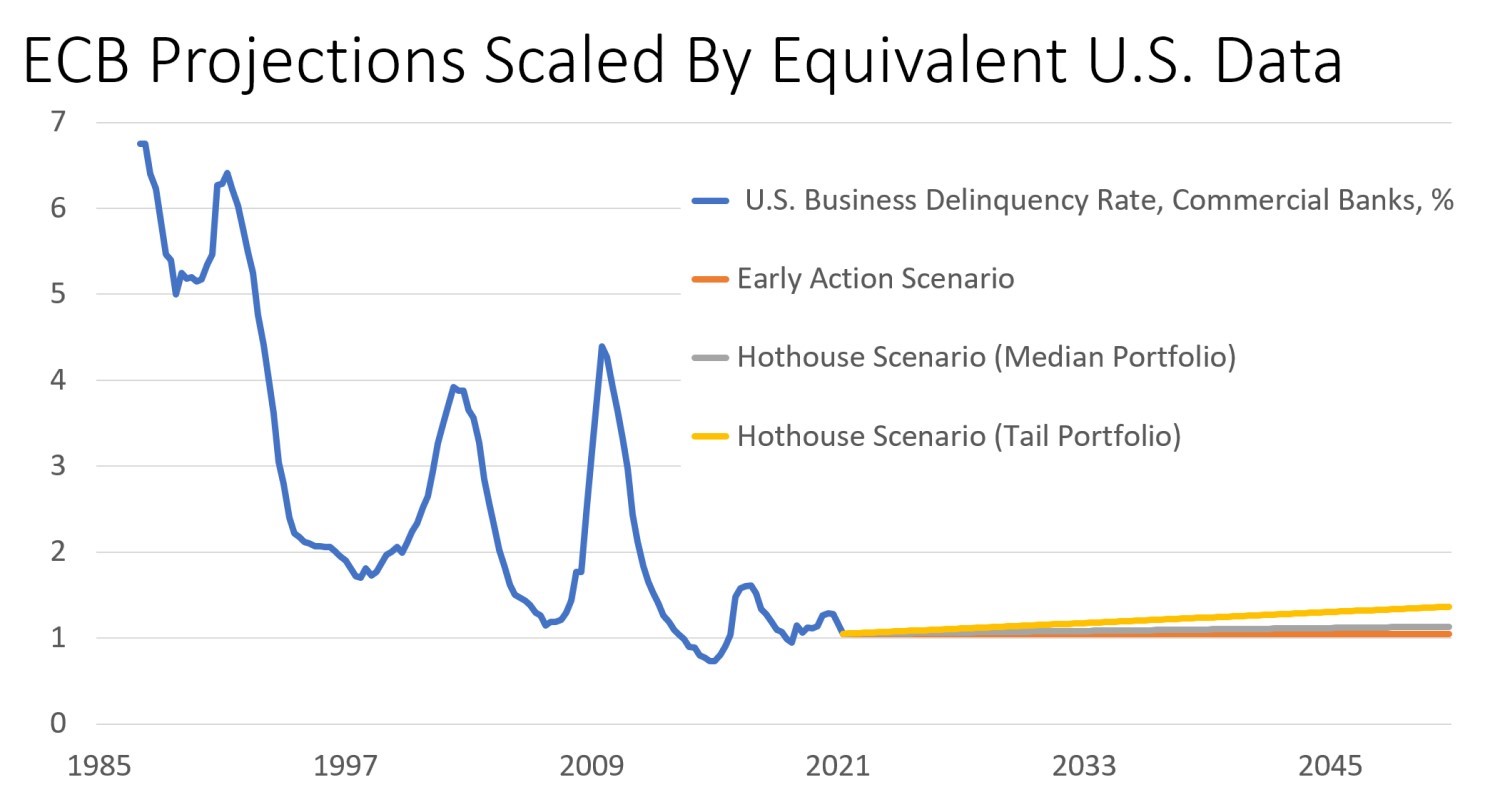

To illustrate how mild these deviations are, between Q1 2015 and Q4 2016, U.S. commercial and industrial delinquencies rose from 0.73% to 1.61% by volume. This was an increase of 120%, which was 17 times more disruptive than the ECB's reported PD delta for the median portfolio. Most, though, will not remember the 2016 “mini-recession,” mainly because it did not contribute to any major bank failures nor cause any real economic fallout beyond the U.S. manufacturing sector.

So, if the ECB's hothouse world projections prove to be accurate, banks should be able to easily adapt their lending practices and remain close to current levels of loss over the long haul. Putting the ECB's results into perspective, during events like the Global Financial Crisis, increases in corporate risk were of the order of several hundred percent - or even a few thousand percent relative to expansion era averages. It is at these levels of default that the stability of the financial system is truly threatened.

Since the ECB's analysis was data driven, their research underscores a reality that is well understood across the industry. Despite more than 50 years of global warming, considerable (if insufficient) transition efforts and a clear increase in the physical effects of climate change, associated credit losses have thus far been very low. A recent article in The Economist, for instance, stated that “for the most part, the evidence that it (climate change) could bring down the financial system is underwhelming.”

Missing Variables?

To effectively manage the risk associated with climate, it is critical that we understand not only why the ECB's stress forecasts were so mild but also why losses, so far, have been lower than might be expected, given the severe changes that have already occurred to the world's climate.

Perhaps there is an X factor, something we are yet to identify, that has spared us from the worst financial fallout from global warming? If we could identify this missing variable and measure its impact, we may be able to estimate how robust it is likely to be in the future. If it is fragile, losses will climb as the climate crisis deepens and future ECB stress tests will show a much steeper response than that which was just published.

There are many potential candidates for “X.”

One possibility is the historical predictability of physical changes in the environment. A fascinating analysis by CarbonBrief in 2017 considered the accuracy of past temperature projections published by climate scientists. As far back as 1981, forecasts produced by a team from NASA's Goddard Institute predicted 2017 temperatures to within only a few percentage points. The overwhelming majority of early forecasts considered in the CarbonBrief article were equally meritorious.

That said, the link between temperature forecasts and actual physical effects can be somewhat difficult to pinpoint, depending on the time scale of interest. A 2019 New York Times article, for example, pointed out that, prior to the 1990s, scientists tended to understate the physical effects of global warming, believing that measurable changes would only become evident over centuries. Subsequently, in 1993, the publication of a seminal article on Greenland ice cores made it clear that observable change could be far more abrupt, of the order of only a few decades. Since then, predictions of future climate effects have become much more prescient.

For banks and most investors, a decade of warning is effectively a lifetime.

For those with interests beyond a decade, including people who want a better world for their grandchildren or the continuation of the human race, observable change on this time scale has a direct impact on wellbeing. For a CEO looking to upgrade a factory on a floodplain, however, a decade of assurance is probably sufficient, given the rate at which the facility will depreciate and be rendered obsolete. The bank that funds a five-year loan to finance the project will therefore be in the clear long before any climate effects (which were not predicted at the time the loan was originated) are ever realized.

Though there is a lot of talk about global warming, successful investors and decision-makers will generally make use of the best available scientific predictions. For at least the past 40 years, it turns out that such forecasts have been precise at all horizons typically required by investors and banks - and losses are invariably low when bets are placed using predictions that turn out to be correct.

There are also elements of transition that have historically been predicted with a high degree of confidence. While the timing and scale of transition efforts were always very difficult to discern, depending as they did on the vagaries of political will, the nature of past efforts to combat global warming have been much easier to envisage.

For example, an investor in 1980 would have been highly uncertain about whether climate change would ever be addressed. But if it was, most back then had a clear understanding of the broad nature of changes that would follow - including, for example, the promotion of cleaner energy forms and controls on vehicle and industrial pollution. A New York Times editorial from 1979 (“The CO2 Gamble”) even advised investors to favor solar because coal was then viewed as too risky a proposition.

Mapping the Future: The Need for More Clarity

Moving ahead to 2021, we are perhaps more certain than ever that climate change will be addressed in some form. Moreover, we remain clear about the broad nature, if not the detail, of the policies that will be used to combat it. Like our 1980 forebears, however, we have only a vague sense of the speed at which transition efforts will transpire.

Consistent with this reasoning, greater certainty about the future policy roadmap should reduce the potential for financial losses triggered by transition. Those concerned about climate change - hopefully, everyone - are eagerly anticipating the upcoming COP26 Summit in Glasgow.

The summit is expected provide investors with more signals regarding the speed and vigor of future transition efforts. If it succeeds beyond expectations, it will also provide the global community with increased clarity, making it much easier for investors and lenders to pick the right horses as the battle against global warming intensifies.

If the horses are well selected, and if policymakers follow through on their pledges, future financial losses related to the transition will most likely continue to be low.

Parting Thoughts

Despite the tepid nature of the ECB's results on credit, the authors' descriptions of the findings are more exaggerated. For example, the report states that “there are clear benefits to acting early” to address climate change, but the analysis indicates that such efforts will reduce corporate defaults from 2.3% to 2.1%.

The report also declares that a 16% rise in PD would be “extremely disruptive,” but banks often experience annual deviations in default activity that are larger than this during periods of uninterrupted expansion. Lastly, the report states that climate is a “major source of systemic risk,” but the most acutely affected large domestic bank sees hothouse corporate default rise to 3.3% from 2.7% under the benign early-action scenario (see Chart 38 from the ECB report).

For those of us who want a sound financial system under all possible circumstances, the ECB's findings are much more positive than they are purported to be by the report's authors.

Figure 3: The ECB's Climate-Based PD Forecast - Applied to U.S. Data

After all, the report clearly indicates that there is a long runway for us to work with before systemic bank failure is seriously threatened by climate change. This will give us plenty of time to explore the data, test theories (like those posited here) and better understand the scale and nature of the financial risk posed by warming.

Obviously, the length of the runway is finite - if the sensitivity of banks ever tips, it will be in everyone's interest if this can be detected at the earliest possible juncture. Part of our statistical exploration of financial climate risk should therefore involve the development of sensitive early warning systems designed to detect changes in the level of risk quickly.

While the runway exists, the attention of the banking industry can instead be laser focused on ensuring that financial forces are correctly aligned with broader societal efforts to attack climate change. These efforts will no doubt benefit from the presence of a robust financial sector, capable of directing capital toward the most productive applications.

Tony Hughes is an expert risk modeler for Grant Thornton in London, UK. His team specializes in model risk management, model build/validation and quantitative climate risk solutions. He is currently engaged in consulting projects related to climate risk and has contributed a chapter on climate stress testing for an upcoming book. He has also recently participated in leading conferences and other speaking engagements related to climate modeling.