To understand the transmission of distress in the leveraged loan market to the capital markets, one must comprehend how collateralized loan obligations (CLOs) and loan mutual funds work. They are two of the largest types of investors in leveraged loans and are exposed to different kinds of risk.

A CLO is a limited-life securitization vehicle that holds a portfolio of leveraged loans, financing it by issuing several tranches of floating-rate debt securities, as well as an “equity” tranche that pays no stated interest rate but receives residual cash flows. The tranches absorb losses in order of priority, with the AAA-rated tranche least likely to experience losses of principal or interest, and the equity tranche most likely to do so.

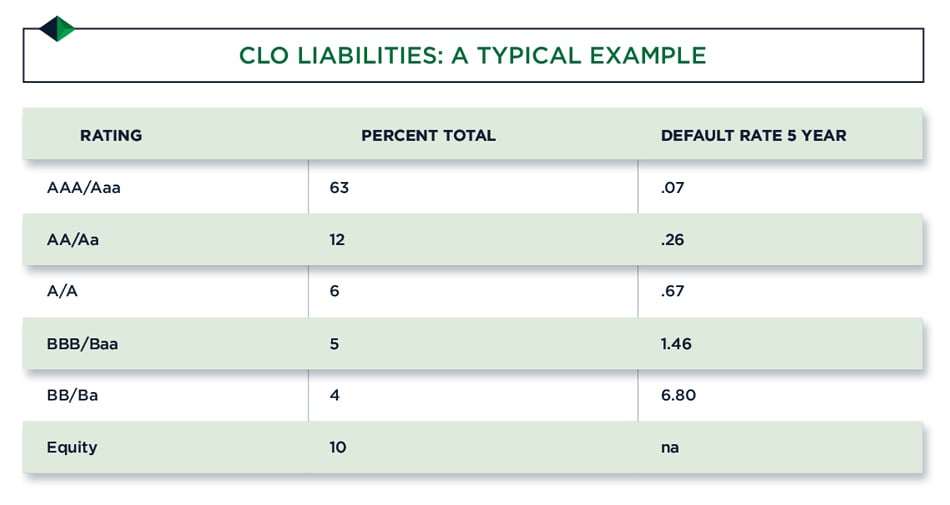

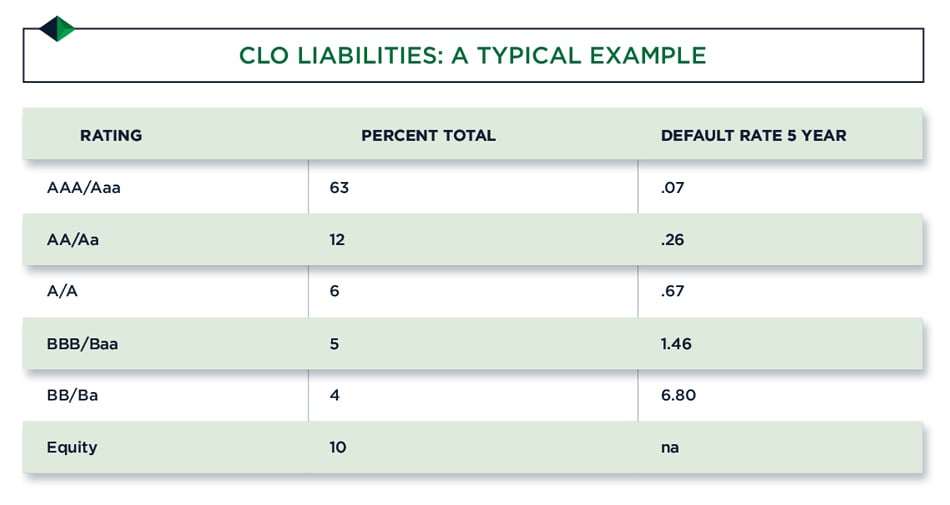

Although the structure of CLO liabilities varies somewhat, a fairly typical case can be seen in the table below, which also depicts Moody’s long-run average, 5-year cumulative default rates on corporate bonds for each grade.

CLO loan portfolios are diversified across issuers and industries, and therefore are fairly likely to experience the average default and recovery rate for all loans issued around the time of CLO creation. CLOs invest almost entirely in leveraged loans that are rated BB/Ba and riskier, with the majority of CLO investments rated in the single-B range at acquisition.

The five-year cumulative single-B default rate is 16.6 percent (about 3.3 percent a year), and the historical average recovery rate on defaulted loans is around 75 percent. With some BB- and high B-rated loans in portfolios, the standard CLO industry assumptions of a 2.5 percent annual average default rate and average annual loss rates of about 0.625 percent are consistent with available evidence.

Given an average spread on the loan portfolio higher than 300 basis points over LIBOR and a weighted-average spread on CLO tranches of less than 200 basis points, all investors in the average CLO in average times will receive all principal and interest; holders of the equity tranche will receive a reasonable annual average return, even after expenses of the CLO.

Cycles, Recovery Rates and Mutual Funds Risk

Credit conditions, of course, are not always average. Indeed, corporate credit losses are cyclical, with a substantial fraction having occurred during just three time periods: 1989-91, 1999-02, and 2008-10.

In the worst episodes, for a bond portfolio with a similar rating distribution to CLO portfolios, cumulative 5-year default rates were not far from 30 percent. With a recovery rate of 75 percent, 5-year cumulative losses would be about 7.5 percent.

CLO equity would lose money under such a scenario, but holders of other tranches would not. Investors in CLO tranches would be nervous and market prices of such tranches would drop below par for an extended period – but would eventually return to par.

The recovery rate assumption is crucial: If recovery rates are far below historical averages for loans, then even holders of investment-grade tranches might suffer losses of principal and interest. For example, a recovery rate of 50 percent would imply cumulative losses of 15 percent, enough to wipe out all non-investment-grade tranches of the typical CLO shown in the table.

Overall, the primary risk for CLO investors is that future credit losses will differ (i.e., higher losses are very possible) from those in the past.

Investors in loan mutual funds face a different type of primary risk: run risk. Though large leveraged loans are traded in broker-dealer markets, liquidity has dried up during past periods of credit distress, leading to large discounts below par.

Loan mutual funds have a liquidity mismatch because they offer daily withdrawals backed by assets that might become illiquid. In an episode in 2018, for example, large withdrawals from loan mutual funds occurred when investors came to believe that interest rates would fall in the future, reducing the value of floating-rate loan funds as an interest rate hedge. But credit conditions were good and secondary markets remained liquid, so the transition was orderly.

In contrast, if outflows are due to concerns about future credit losses, withdrawals are likely to coincide with a loss of liquidity and a reduction in secondary market loan prices, creating conditions ripe for mass withdrawals and dysfunctional secondary markets.