Introduction to Leveraged Loans

A primer for understanding the risks of a complex and evolving market

The leveraged loan market is intricate, and so are the associated risks. To grasp the risks borne by investors, the financial system and the economy, one must first comprehend the instruments, the investors, the market and its history.

The term “junk bond” first appeared in the 1980s. It described the new, sizable original-issue market for bonds rated below investment grade (riskier than BBB-/Baa3) that was pioneered by Drexel Burnham Lambert.

In the late 1980s, the syndicated loan market grew rapidly and served many below-investment-grade borrowers. However, loans were not rated for many years and market participants needed a term to indicate riskier loans that were the equivalent of below investment grade. They chose “leveraged loans.”

Despite the name, the determinative feature of a leveraged loan was not the indebtedness of the borrower, but the interest rate spread on the loan. Though the cutoff varied somewhat with market conditions, a spread of 125 to 150 basis points over LIBOR was often close to the line. Today, many loans are rated, and a loan’s rating plays a role in determining whether it is a leveraged loan.

A leveraged loan is usually a package of loan instruments, including a line of credit and one or more term loans – i.e., loans funded at origination with a fixed term to maturity. Where multiple term loans are included in a package, they are often designed to appeal to different investor types by, for example, varying in their term to maturity. The typical package is governed by a single loan agreement.

Leveraged loans are usually floating-rate instruments, with LIBOR as the base rate and an interest rate spread over LIBOR that varies with the credit risk that loans pose. Because it is floating-rate, a leveraged loan contract usually allows prepayment at any time with minimal penalties. Refinancings are common, so compensation received by investors for risk in their leveraged loan portfolio falls as the credit cycle progresses and spreads fall.

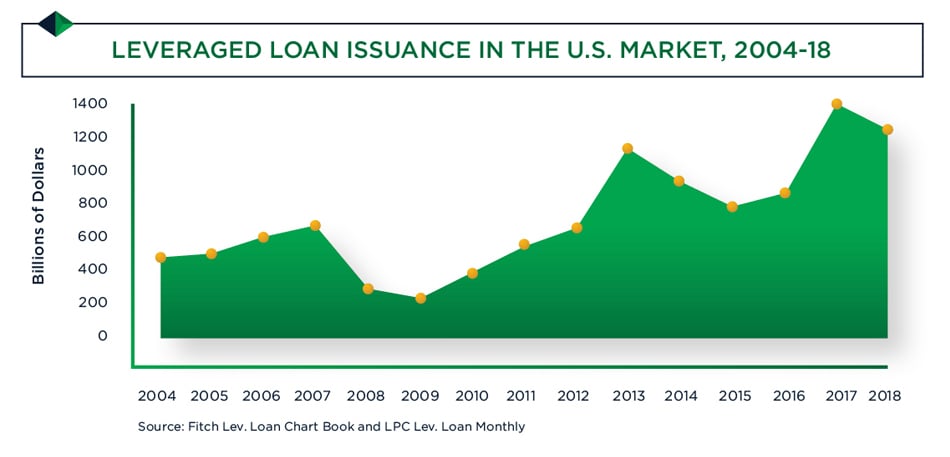

Frequent refinancing explains another feature of the loan market: Annual issuance is large relative to outstandings until the credit cycle turns down. At that time, issuance collapses because firms with outstanding loans already have spreads far lower than they would pay in the now-riskier market.

The chart (below) displays an estimate of the annual amount of leveraged loans issued in the U.S. market. Thomson Reuters’ Loan Pricing Corporation (LPC) estimates that refinancings accounted for two-thirds of issuance in 2017. High rates of refinancing imply that the usual life of a leveraged loan is much shorter than typical contractual term to maturity (3 to 5 years for lines of credit, and 5 to 7 years for term loans).

Recovery Rates, Covenants and Investors

Leveraged loans are usually secured and all tranches of a package usually share the same collateral. Being secured does not offer lenders much protection against default, but, in most cases, secured status places them nearer the head of the line in bankruptcy for recovery of what they are owed; consequently, recovery rates are better than for (usually unsecured) bonds.

In the past, average recovery rates on loans were far higher than recovery rates on unsecured credit. Shared collateral also motivates loan investors to act collectively whenever their incentives are similar.

Leveraged loans have traditionally had many covenants. The two most relevant kinds are maintenance and protection covenants.

Maintenance covenants typically feature allowable ranges for financial ratios or other risk measures; if measures move outside the ranges, the borrower must negotiate with the lender to change the covenant, often paying a fee. If such negotiations fail, the lender can demand immediate repayment of the loan (“acceleration of maturity”), which often forces the borrower into bankruptcy.

Protection covenants typically limit the borrower’s ability to take actions that would substantially increase risk borne by the lenders; for example, by selling assets and not using the proceeds to pay down debt.

However, revisions in both maintenance and protection covenants have changed the risks of leveraged loans. The risks posed by leveraged loans to the financial system depend not only on the risk characteristics of individual loans, but also on the vulnerability of different investors.

Even in the early years of the leveraged loan market, investors included nonbanks, such as finance companies and insurance companies. Today, the majority of leveraged loans, particularly term loans, are bought by collateralized loan obligations. Retail mutual funds specializing in loans also are important investors, while banks continue to be the primary investors in lines of credit.

Though leveraged loans are not securities and are not registered with the SEC, secondary market trading of an investor’s portion of a loan has always been possible, if the investor can find a buyer. (Often, the buyer is another member of the syndicate.)

Organized broker-dealer trading of loans did not begin in earnest until the early 2000s. Today, many investors depend on secondary market liquidity to support management of their portfolios. However, liquidity typically dries up during credit downturns (with prices falling below fundamental values), so investors sometimes find it difficult and costly to sell loans.

This overview has focused on features of the leveraged loan market that are particularly relevant for risk. To learn more about these features, please read our leveraged loan companion articles on maintenance covenants, protection covenants and CLOs.

About the Author

Mark Carey is the co-president of the GARP Risk Institute. In this role, he helps lead research and thought leadership for GARP and the broader risk community.

Currently, he is also an editor of the Journal of Financial Services Research and a co-director of the National Bureau of Economic Research’s Risks of Financial Institutions Working Group – a mixed group of academics and financial professionals that focuses on risk management.

Prior to joining GARP, he was associate director in the Division of International Finance at the Federal Reserve Board in Washington, D.C., leading some of the Fed’s work on issues related to the financial services industry, systemic risk and the financial crisis. He has written many technical papers on credit risk and corporate finance.

Protection Lite and Investor Risk in Leveraged Loans

By Mark Carey

•Bylaws •Code of Conduct •Privacy Notice •Terms of Use © 2024 Global Association of Risk Professionals