- FRM

- SCR

- Risk & AI

- Membership

- Insights & Events

- About Us

Misconduct is one of the most significant symptoms of cultural failure and examples of it have been rife in the financial services sector over the past 10 years. What are its common causes and potential lessons?

From a regulatory perspective, the belief that culture and conduct risk are inextricably linked has been made clear. The UK's Financial Conduct Authority has stated that culture is a priority area and has made no secret of its view that the conduct failings of recent years have been driven by the culture of financial services firms. The Financial Stability Board, moreover, recently published a toolkit on mitigating misconduct risk including cultural drivers of misconduct.

William Dudley, former President and CEO of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, captured the significance of misconduct during a banking culture panel he participated in last year. “I think there's a pretty broad acceptance of the notion that regulation and compliance only takes you so far, and that bad conduct really does undermine the effectiveness of the financial system, because it basically reduces trust,” Dudley said. “You need a good regulatory regime supplemented by various good conduct and culture in the organizations.”

Whether or not an organization is subject to the expectations and scrutiny of a regulator, there is widespread acceptance that achieving the ‘right’ corporate culture can go a long way toward helping to manage risk. A core part of risk management is developing a corporate culture where expectations as to behaviour are clear, appropriate behaviour is rewarded (and inappropriate behaviour punished) and employees are empowered to speak up if they spot an issue.

Faced with the need to focus on culture, an obvious question is where to start. There is a rich body of academic and regulatory material on culture, and a range of views on how best to measure and influence culture in the workplace. Given that culture is a behavioural set of norms, some firms are looking to behavioural science to predict and measure cultural drivers as part of their assurance processes.

As lawyers at an international law firm, we have a wealth of experience in investigations and have seen first‐hand the consequences of misconduct, including, for example, regulatory breaches and boardroom disputes.

Drawing upon our experience of investigations across a range of sectors and geographies, we recently carried out an empirical analysis of the underlying cultural factors that may have allowed misconduct to take place, whether as a direct cause or by creating an environment in which misconduct was able to flourish.

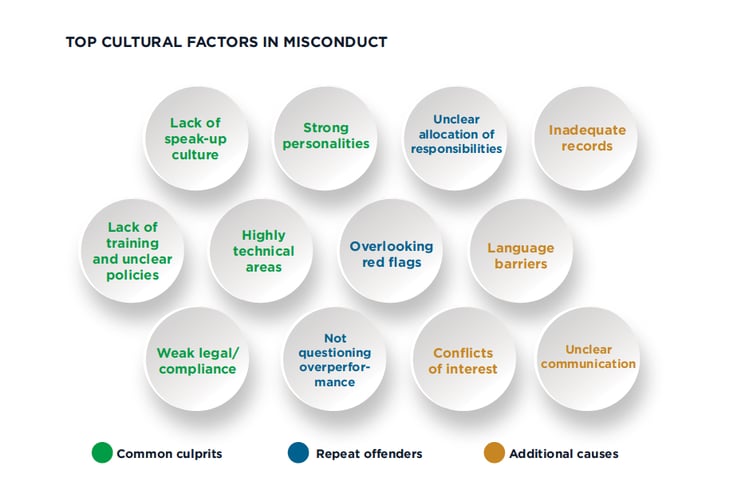

We identified 12 cultural factors present in environments in which misconduct or other problems occurred. The 12 factors identified through our research are grouped into three categories, depending on the frequency with which they arose.

There are many examples of each of these factors arising in practice and there is frequently a degree of overlap between them. Not all of these factors can – or should, necessarily – be eliminated. Instead, the focus should be on identifying whether they are present, considering what risks they may pose and deciding what steps could be taken to reduce those risks.

Let's now focus on 3 of the 12 factors that most commonly arose: strong personalities; lack of speak‐up culture; and highly technical areas. What's their impact, and what actions can be taken to reduce the risk that they pose?

The presence of strong personalities within a business is almost inevitable. Successful leaders tend – and often need – to have strong personalities. This can bring with it many positives, such as the ability to drive change, motivate and inspire.

The potential risky behaviour that we have seen arising around strong personalities includes excessive deference from junior staff, and a lack of challenge or scrutiny from the oversight and control functions. (When an individual has handpicked subordinates, who see their loyalty as being to their manager rather than to the organization, the former can be particularly problematic.)

Inadequate challenge and scrutiny can often arise in smaller overseas offices. In such locations, distance from head office can have an impact on the degree of oversight that is exercised and the extent to which local employees feel there is anything they can do to raise their concerns.

Closer to home, these obstacles may arise in businesses where a particular individual has had a huge amount of success and is highly respected, to the extent that no‐one contemplates that they might be doing something wrong. Consequently, red flags may be overlooked.

Alternatively, employees may feel that very charismatic, respected and successful senior people (particularly those who have a close relationship with management) are untouchable. Indeed, there may be a ‘culture of fear’ or ‘cult of personality’ around such people – or a belief that concerns will not be taken seriously, even if they are raised.

The culture of fear can also impact the risks that team members are prepared to take. We have seen examples of a domineering personality who focusses on the business outcome he or she wants to achieve, and then leaves others to work out how to achieve it. The fear of failing to meet that challenge may then lead more junior employees to take inappropriate risks to achieve results.

Where there is a strong personality driving teams to achieve results, the importance of a strong second line of defense is heightened. However, there may be significant pressure on legal and compliance not to stand in the way of business results, and executives in the second line may be pushed to answer a very narrow question (“Is it legal?”), rather than stepping back to ask whether something is appropriate or gives rise to other concerns.

Given that the presence of strong personalities in the business world is inevitable, the challenge for companies is to identify where their own strong personalities sit; be aware of the risks that can be created by those strong personalities; and think about how to manage the risks. This may require a combination of robust challenge or oversight from other strong personalities; a strong second line of defence; proper appraisal and development of strong personalities as they rise up the corporate ladder; and a strong speak‐up culture, with routes for reporting and escalation that allow employees to raise their concerns anonymously and/or to bypass any perceived allies of the strong personality.

When evaluating an organization's governance structures, consideration must be given to both the roles in the structure and the individuals who fill them. This is crucial to governance effectiveness.

Unfortunately, “whistleblowing” does appear to have an image problem – a lot of the headlines around whistleblowing are either framed in a relatively negative light, or suggest that it is an act with significant consequences.

Concerns that blowing the whistle may result in a formal investigation and the involvement of legal and compliance may be off‐putting. Alternatively, employees may be mindful of incidences they have seen of whistleblowing being “weaponized” – for example, being used cynically to attack (potentially legitimate) redundancy or performance management exercises and increase a departing employee's negotiating leverage. This image problem can lead to a real reluctance to raise concerns.

Fear of negative consequences may also be a significant factor in generating a reluctance by employees to raise concerns.

In a survey carried out by Freshfields of 2,500 managers across the US, Europe and Asia, almost one in five respondents said that they thought the average employee would expect to be treated less favorably if they blew the whistle. Moreover, 55% of respondents thought that concerns about damage to reputation and career prospects would prevent whistleblowing in their organization. The negative consequences feared by whistleblowers may often be more perception than reality – but in either case, the impact on speak-up culture is significant.

Trying to strengthen speak-up culture is a focus for many organizations. They appreciate the importance of issues being brought to their attention early – and, ideally, being flagged to them directly. However, transforming this aspect of an organization's culture can be a slow process, and the harm done by whistleblowers who feel ignored or neglected can be extensive.

In many cases, whistleblowers may believe incorrectly that their concerns have been ignored (simply because they are not told otherwise), so improving feedback processes can be an important tool in trying to overcome the ‘futility’ factor.

Organizations may need to think not just about ‘speak up’ but also ‘listen up’ – for example, training managers on what to do if employees raise concerns with them, so that they respond appropriately. Indeed, it's helpful to encourage managers (especially those who are viewed as strong personalities) to demonstrate openness and responsiveness to employees who raise concerns. This can be made part of the appraisal process – to really test whether they are demonstrating the required behaviour.

Other options include rewarding employees who have spoken up – either through financial rewards, recognition in their appraisals or even just a simple “thank you” from senior management.

Striking the right balance in relation to feedback is difficult. The issues raised by a whistleblower may be sensitive, and, in some cases, could be the subject of regulatory or even criminal proceedings. What's more, confidentiality is a requirement in certain jurisdictions, and disclosing details of the outcome of an investigation could involve divulging confidential or business‐sensitive information.

For all of these reasons, businesses are typically unable or unwilling to recognize “compliance champions” publicly. However, even a high‐level response – an acknowledgement of receipt, a confirmation that an investigation has been or will be undertaken, or an expression of thanks for raising the issue – may go a long way to overcoming the perception that speaking up is a pointless exercise.

As with strong personalities, it is inevitable that some businesses will have areas that are highly technical. This is not, intrinsically, a problem.

However, the risk that can arise is that if, say, a particular product or business is extremely technical, only a few individuals will be able to understand it fully. This, in turn, can mean that problems are harder to spot.

In the course of our investigations work, we have seen examples of products having been developed that were so complex that the risk committee members who were responsible for approving them did not fully understand the overall product. (While particular members may have understood aspects of the product, there was no individual who could step back and understand the whole.)

In another case, the only individual on the risk committee who understood the product completely had also been involved in its design and had a financial interest in its success, giving rise to a conflict of interest.

Where something is highly technical, there is also a question around the level of delegation that may be appropriate – as well as who should be responsible for seeking the necessary legal or compliance sign‐off.

Junior employees who are tasked with seeking legal advice on a complex product or strategy, may lack a thorough understanding of it. In turn, they may not ask the correct questions of the legal team. Combined with, say, a failure by the legal team to probe further and to ensure that they fully appreciate the context, such inadequacies could result in failure to identify a major regulatory breach.

Eliminating complexity is unlikely to be a practical answer to this potential risk factor, so businesses need to consider what else they can do to manage the risk created by highly‐technical areas. This might include, for example, giving thought to whether the risk committee or compliance team is staffed by individuals with sufficient technical expertise – and whether those with the technical expertise also need training on the wider regulatory and reputational considerations.

Organizations can also seek to ensure that the importance of asking questions is understood and accepted. When an area needs more explanation, senior managers should take the lead in saying “I don't understand” – and should encourage all of their team members to do the same.

It is incredibly important to continue to learn lessons from the problems that arise, while simultaneously thinking about everyday steps that can be taken to manage the sources of risk that have been identified.

‘Lessons learned’ exercises tend to focus on one particular issue, instead of looking holistically across a range of issues. The tendency in the aftermath of a crisis is to focus on the immediate conduct and systems and controls issues, rather than the impact of the corporate cultural environment in which the problems occurred.

Standing back and looking holistically at the organization's recent (and more historic) experience is likely to be more culturally revealing. This exercise may yield factors like the 12 cited earlier in this article, offering valuable data points to look at in developing culture in a practical and meaningful way.

It is important to remember that corporate cultures are not always simply ‘good’ or ‘bad’ – particular features can have both positive and negative consequences. For example, collaborative and supportive environments may be rewarding to work in, but also make individuals reluctant to challenge others or have difficult conversations with underperformers who make mistakes and expose the organization to regulatory risks.

The key for organizations is to identify the risks or vulnerabilities arising from their own corporate culture and to think in practical ways about how to address those.

Having identified their list, as they move toward managing risk, firms can then ask themselves important questions at all levels, from the board to middle management. For example, we have a whistleblowing policy and a hotline, but what do our employees really feel about whistleblowing? We know we have a strong personality in this area of the business, so who is the counter to that person? From a risk and compliance perspective, who really understands the technical aspects of the business and can provide the right scrutiny?

Using past experience to think about culture, and to ask the important questions, can play a vital role in developing a culture‐focused risk management strategy.

About the Authors

Caroline Stroud is a partner in the Global Investigations practice at Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer LLP. She specializes in workplace investigations into misconduct and has extensive experience in reviewing whistleblowing procedures, conducting “lessons learned” exercises and analyzing culture within a business.

Emma Rachmaninov is a regulatory partner in the Financial Institutions Group at Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer LLP. She regularly advises financial institutions on culture and governance matters, including in relation to the UK's Senior Managers and Certification Regime.

Holly Insley is a senior associate on the People and Reward team at Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer LLP, and a member of the Global Investigations practice. She advises financial services clients on executive remuneration issues, hiring and firing and the investigation of suspected misconduct.

By Jo Paisley

Creating Effective Incident ReportingBy Dr. Mike Humphrey

•Bylaws •Code of Conduct •Privacy Notice •Terms of Use © 2024 Global Association of Risk Professionals