A year with record-breaking temperature, heatwave, wildfire and ice melts occurring across the globe, 2023 marked the first time in history that global temperatures have been 1.5°C warmer than pre-industrial times. This fact also increases the chance that there will be a rapid transition to a low-carbon economy in response to escalating physical risks.

A recent ECB paper suggests a further incentive for a faster green transition — that it would benefit firms, households and banks, while significantly reducing medium-term costs. This combination of physical and monetary drivers suggests that we may see more ambitious climate mitigation action, which could increase companies’ financial risks.

In the run up to this year’s COP, we explore some of the nuances of measuring emissions, how reductions in emissions might be misinterpreted or misrepresented and why a fast transition is critical to minimizing the physical risks from climate change. (To find out more about how COPs work, listen to our Climate Risk Podcast episode with Nigel Topping)

What Needs to Reduce by When?

To meet the Paris Agreement requirements, a global 45% reduction in net carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions (from 2010 levels) is needed by 2030, and a 100% reduction by 2050, according to the IPCC. Other non-CO2 greenhouse gases, such as methane, and particles like black carbon also need to reduce though by a different amount: 35% by 2050.

Maxine Nelson

Maxine Nelson

It is important to also measure aerosols, which are often produced at the same time as greenhouse gases, because they lower global temperatures. Consequently, reducing some greenhouse gases may have a minimal net impact on the global temperature for two-to-three decades (an immediate benefit is a reduction in air pollution). This means that if non-CO2 emissions aren’t counted, the remaining greenhouse gas budget may be overestimated.

China is a notable country whose recent Paris Agreement commitment has differentiated CO2 and non-CO2 emissions. Its commitment is phrased in terms of CO2 emissions peaking before 2030 and achieving carbon neutrality by 2060, and separately mentions tightening regulations over non-carbon dioxide emissions.

The Path to Net-Zero Makes a Difference

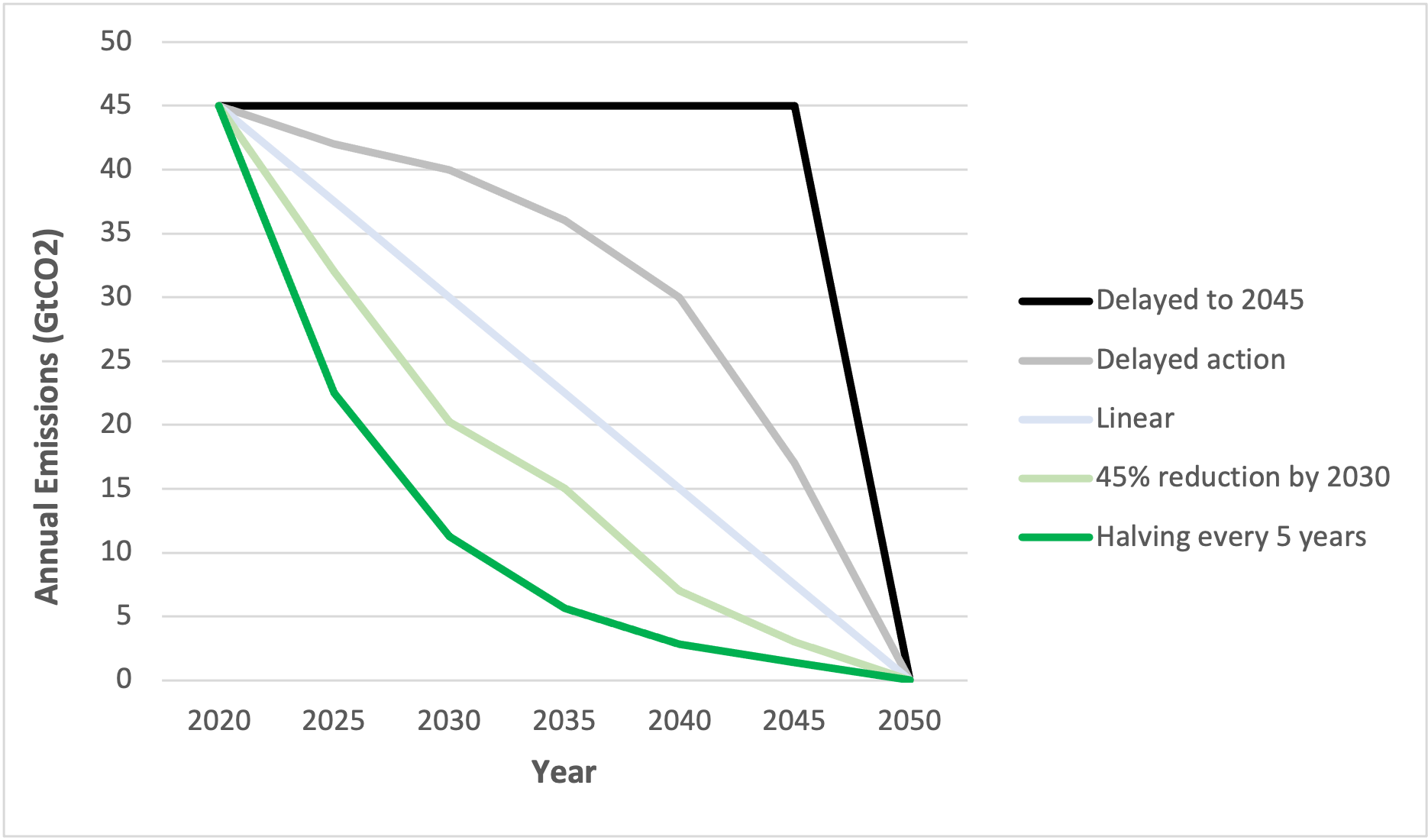

How we get to net-zero by 2050 matters, as the stock of greenhouse gases determines the amount of global warming. As long as there is an annual flow of emissions, the stock continues increasing and the impacts of global warming are exacerbated.

According to estimates from the IPCC, as of 2020, we have a remaining global carbon budget of 500 GtCO2 to maintain a 50% chance of staying within 1.5°C of global warming. 2019 emissions were estimated to be about 45 GtCO2. If this level of emissions continues, the entire budget will be used by 2030. In fact, to stay within budget, emissions need to more than halve every five years from now until 2050.

Figure 1 Annual CO2 emissions per year

However, if emissions reduce rapidly year on year, there should be some remaining carbon budget. This is a good thing, as scientists have said that there may be 100 Gt of emissions from phenomena like melting of permafrost and methane released by wetlands, which aren’t yet accounted for due to the uncertainty of their magnitude.

We also know that even though there will be a slowdown in the temperature increase when we get to net-zero, the physical changes in the world will continue, and therefore physical risks will continue increasing.

The Difference Between Absolute and Intensity Reductions

One other measurement nuance to watch out for is whether a reduction in emissions is an absolute figure, or presented as a reduction in intensity. To reach net-zero by 2050, absolute emissions need to reduce.

However, some companies and countries present their reductions in terms of carbon intensity per products manufactured, or per amount of GDP, respectively. They might do this to show that they are getting more efficient, emitting fewer greenhouse gases per unit of production. It may also be done to avoid misinterpreting emissions from more durable products that have a longer life, according to the GHG Protocol.

India is one country which specified its emissions reduction goal in terms of intensity – pledging a 45% reduction in emissions per unit of gross domestic product (GDP), by 2030. While it is starting from a low base – with average energy consumption a third of the global average – this does mean that its total emissions may increase as GDP continues to increase.

Parting Thoughts

When reviewing the transition plans of countries or corporations, it’s important to look at the details to fully understand their ambition. A plan that looks ambitious at first glance may not actually be so if it only addresses some of the emissions, plans to have all the reductions many years in the future or is based on emissions intensity while increasing absolute emissions. Each of these can increase the physical and transition risks that the entity is exposed to and make them a higher-risk counterparty.

Maxine Nelson, Ph.D, Senior Vice President, GARP Risk Institute, currently focusses on sustainability and climate risk management. She has extensive experience in risk, capital and regulation gained from a wide variety of roles across firms including Head of Wholesale Credit Analytics at HSBC. She also worked at the U.K. Financial Services Authority, where she was responsible for counterparty credit risk during the last financial crisis.