CRO Outlook

Friday, June 18, 2021

By Brenda Boultwood

How much risk would you be willing to accept to meet your company's performance objectives, if you were a board member of a CRO? Moreover, what types of limits, if any, would you place on organizational missions to stay within prescribed risk boundaries?

These are the types of questions that must be asked and answered, particularly with financial institutions today facing certain risks that simply cannot be mitigated. An intelligent response starts with an understanding of risk appetite and risk treatment.

Risk appetite can be defined as the types and amount of risk an organization is willing to accept in pursuit of business objectives. Risk treatment is the process of selecting and implementing actions to modify risk through mitigation, sharing, avoidance or acceptance.

The CRO will typically represent the organization's management team in proposing a risk appetite level to the board. The board will have the opportunity to question and modify these risk appetite statements, as they consider whether the risk levels are adequate to achieve the organization's strategy. Subsequently, the board will then approve the risk appetite, based on their gut feeling about the level of risk appropriate for the organization.

The CRO will then take the approved risk appetite and cascade it down through the organization through limits (maximum or minimum thresholds) and policies - for regulatory compliance, employee misconduct intolerance, etc.

Decisions made by the CRO and the board are based partly on business performance projections. In March 2021, we linked business performance management to human capital management. This process requires the establishment of an organizational strategy and a risk appetite to evaluate business plans and prioritize investments.

Top-down and bottom-up planning must be dynamically integrated, while respecting periodic board delegations of authority for capital spending and risk-taking. Most other variables change in real-time, as experts reassess risk tolerances and triggered actions.

Figure 1: A Dynamic Business Planning Process

Develop a Risk-Taking Philosophy

What is your firm's attitude toward risk? The businesses in which a company chooses to invest are directly tied to the level of risk its willing to accept - and that's why the development of an effective risk-taking philosophy is so important.

A financial organization with a lower risk appetite might choose to avoid, say, a fintech partnership opportunity that is perceived as riskier but offers greater returns. In contrast, a different financial organization with a high-risk appetite might decide to accept, for example, cryptocurrency payments - even though the value of future crypto transactions could potentially be wiped out by changing regulations. The rewards in the latter risk-appetite scenario may be high, but so, too, may be the risks.

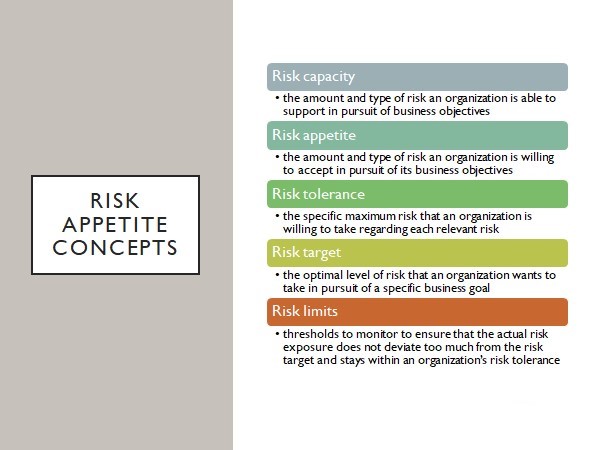

Risks and opportunities can only be balanced if a company has a clear understanding of its risk appetite. Risk capacity, tolerance, targets and limits all must be considered during the development of a risk appetite statement. Figure 2 details how these different risk levels can be defined.

Figure 2: Risk Appetite Terminology

Risk Appetite: Key Components

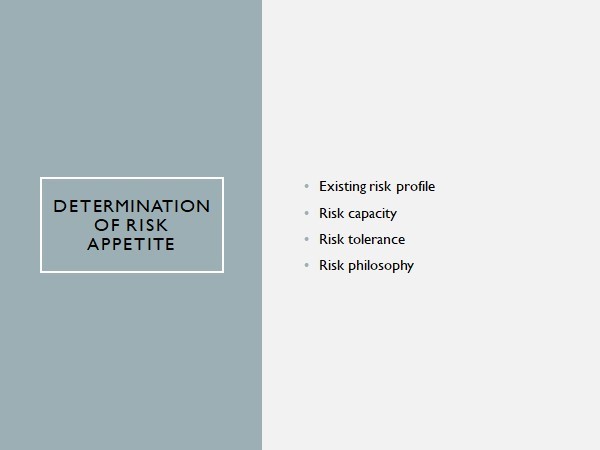

Several factors play a role (see Figure 3) in determining an organization's risk appetite.

Figure 3: Determination of Risk Appetite

Inherent risk levels can be reduced through mitigation or insurance, while, say, a dangerous risk (or a risk with limited return on investment) can be eliminated by stopping the activity. Alternatively, when risk reduction is too expensive or impossible, a risk can be accepted as the cost of the organization's strategy.

Risk appetite will vary depending on the type of activity. For example, an organization's lowest risk appetite may relate to cybersecurity, data privacy, health, safety and compliance risks. A marginally higher risk appetite may exist for strategic priorities, such as new product developments and geographic market expansion.

This means a budget may be evenly split between, say, larger investments in human capital (to support strategic products and markets) and smaller investments in projects (like control enhancements) with a low risk appetite. Either way, the risks must be acknowledged and deliberately mitigated - or accepted.

Required Risk Acceptances

Sometimes, a risk that cannot be avoided, reduced or transferred must be accepted. Below are some examples of known and unknown risks that cannot be treated.

Untreatable Known Risks and Unmonitored Risks

Tail risks are examples of known risks that are perceived to be so remote that it makes no sense to spend resources on mitigation.

Unmonitored risks, on the other hand, are hazards that management chooses not to identify or monitor proactively. An example could be third-party risks arising from vendors, contractors and other third-parties that are not monitored - such as power producers in, say, Texas, or a contractor sending emails to an unsecured email.

Binomial Outcome Risks, Uncertainty and Contagion

When an organization's mission is inherently risky and investors understand the relative risk of success or failure, hazards are referred to as binomial outcome risks. Examples include pandemic vaccine development, driverless cars and space missions. Some might call these moonshot risks.

In other cases, the full examination of the risks and benefits is not possible. For example, unknown risks are not treatable and could include uncertainty, unknown unknowns, or unidentified risks (often called black swans). The latter are events that are impossible to predict and have a major impact, yet often appear obvious with hindsight.

Examples of black swan events include the 9/11 attacks, the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, the dot-com bubble of 2000, Brexit (2016) and COVID-19. These types risks are not inherently unpredictable, but are typically not foreseen, because of factors like inexperience, bias and outside noise.

Contagion risks happen when multiple breakdowns simultaneously occur (with each separately treatable), triggering a large failure.

Acceptance Methods

Untreatable risks require risk acceptance, which typically occurs in one of two ways: ex-post surprise and ex-ante identification.

Ex-post surprise entails a situation where the risk owner claims he or she had no idea the bad outcome was possible. When the risks of a business are either misunderstood or ignored, such a claim is typically valid. (Neither situation is optimal, however, because misunderstandings and ignorance are equally bad.)

Ex-ante identification entails a situation in which known risks are acknowledged and accepted, via tail risk assessments, scenario analysis or planned control investments. Regular, end-to-end risk self-assessments of business processes are simple approaches for identifying and measuring risks.

Proactive ex-ante risk identification is clearly superior to ex-post surprise.

Parting Thoughts

Connecting bottom-up business planning to top-down strategic planning can be achieved with the help of a well-defined risk appetite.

Management, moreover, can determine where high-level risks reside through strong risk identification. When a risk cannot be mitigated, insured or abandoned, it must be accepted.

Brenda Boultwood is the Director of the Office of Risk Management at the International Monetary Fund. The views expressed in this article are her own and should not be attributed to IMF staff, Management or Executive Board.

She is the former senior vice president and chief risk officer at Constellation Energy, and has served as a board member at both the Committee of Chief Risk Officers (CCRO) and GARP. Currently, she serves on the board of directors at the Anne Arundel Workforce Development Corporation.

Earlier in her career, Boultwood was a senior vice president of industry solutions at MetricStream, where she was responsible for a portfolio of key industry verticals, including energy and utilities, federal agencies, strategic banking and financial services. She also previously worked as the global head of strategy, Alternative Investment Services, at JPMorgan Chase, where she developed the strategy for the company's hedge fund services, private equity fund services, leveraged loan services and global derivative services.

•Bylaws •Code of Conduct •Privacy Notice •Terms of Use © 2024 Global Association of Risk Professionals