Credit Edge

Friday, October 9, 2020

By Marco Folpmers

In the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis (GFC), economic capital (EC) - a popular tool for calculating capital requirements across different risk types - fell into disfavor at some banks. Projecting the level of EC needed for extremely rare events was seen as quite difficult, and aggregating capital calculation crosswise credit risk, market risk and operational risk was a major challenge.

But amid the pandemic and the pending implementation of revised bank capital rules (commonly known as Basel IV), banks have seen the need for more granular capital approaches - especially for credit risk. Consequently, EC has experienced something of a renaissance.

Before delving further into the pros and cons of EC, the reasons for its rebirth and its potential future role, it's helpful to offer a quick explainer.

Defining Economic Capital

EC is a risk measurement tool for calculating capital requirements for credit risk, operational risk, market risk and interest rate risk in the banking book. Essentially, it determines the amount of a capital a bank needs to hold to support any risk it takes, and is meant to cover “the full universe of risks that may have a material impact” on a bank's capital position.

EC calculations are typically performed through tailor-made internal models, rather than regulatory approaches. The single risk-type EC amounts are aggregated to an overall amount that takes inter-risk diversification into account.

EC calculation is part of banks' compliance with the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision's Pillar 2 requirement - also known as the supervisory review process. For credit risk, under Pillar 2, special attention is paid to credit concentration risk - i.e., the co-occurrence of credit loss events due to common or systematic risk drivers. This credit concentration risk is captured only in very crude way in regulatory capital (RC) calculations.

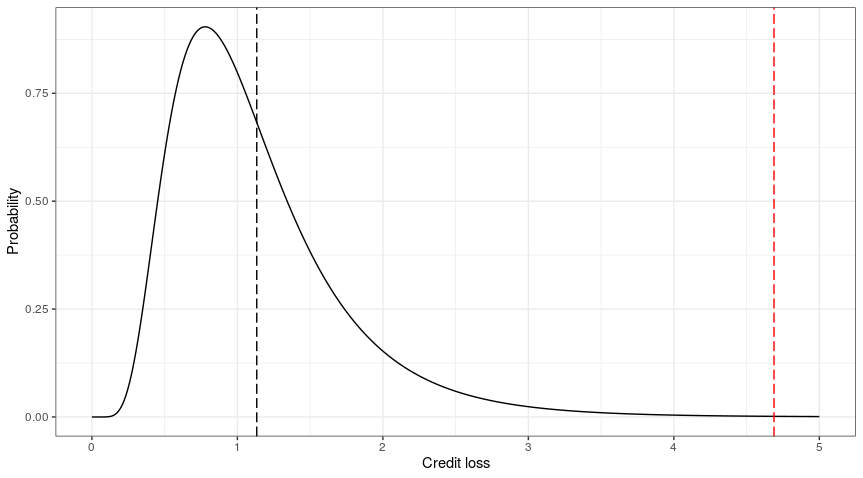

Single-risk EC amounts are determined with the help of value-at-risk (VaR) calculations. This is illustrated for credit risk in the figure below.

VaR is calculated with the help of the statistical loss curve, and equals the difference between a very high percentile credit loss (illustrated above for the 99.9th percentile, with the help of the dashed red line) and the expected loss (the dashed black line). The high percentile is chosen in such a way that the targeted rating of subordinated debt is protected.

The higher the targeted rating of subordinated debt, the larger the confidence level for the VaR calculation. Typically, confidence levels of 99.9%, 99.95% and 99.99% would be used for subordinated debt rated A, AA and AAA, respectively.

EC should not be confused with RC, which is the amount of capital that a bank needs to comply with regulatory guidance and rules. Whereas RC is easier to calculate and more easily compared across banks, EC allows for bank-specific methodologies, especially to distinguish between systematic drivers for credit risk (e.g., sector developments) and idiosyncratic drivers (e.g., a declining debt service coverage ratio). This makes EC much better informed than the single-risk driver Vasicek model that underlies a typical RC calculation.

Global Financial Crisis Illuminates EC Deficiencies

The GFC made risk professionals rethink the added value of EC. In short, it was not sufficiently robust to anticipate the capital erosion that would take place after the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers in September 2008.

But the issues run deeper. After the crisis, risk professionals started thinking about a very high confidence limit of, say, 99.95%. The question then arose: What does it mean to calculate the capital needed to protect against an event that occurs only 0.05% percent of the time?

Apparently, the probability that a bank's capital is not sufficient for such an event is 1 out of 2,000 - but what's the narrative behind this? For sure, it doesn't mean that we're safe for the upcoming 2,000 years. Consider a scenario in which, over the next 12 months, 2,000 extremely rare events are possible, with an equal probability to occur; under such a scenario, a bank's capital level would not be sufficient in only one of those instances.

Taking this into consideration, was the subprime crisis truly a 1 out of 2,000 event? Did these odds, moreover, also apply to the COVID-19 pandemic?

If our answer to both of these questions is “yes,” does this mean we have experienced two extraordinarily rare events (1 out of 2,000) in the past 12 years? Alternatively, since EC models were calibrated on pre-COVID-19 data, do we have to consider the pandemic in a completely different light?

In short, it is hard to identify the level of capital needed for a highly improbable event, and to then distinguish between foreseen extreme events and disruptions outside the space of the model assumptions and environment. Moreover, it is very difficult to calibrate the EC model for a certain set of obligors in a given regime or time frame (say, pre-COVID-19) and then extrapolate (to post-COVID-19).

Finally, aggregation across risk types remains a problem. It is difficult, for example, to determine the diversification benefit between credit risk and operational risk. Many approaches have been suggested (VAR-COVAR, copula, integrated approaches) to calculate the diversification benefit, but this remains a potential pitfall of EC.

Overall, the perceived usefulness of EC calculations had deteriorated since the GFC - that is, until 2020.

Reasons for the Return of EC

This year, EC has experienced a revival. One of the reasons that it is back is the move toward simplification within the RC domain. Since the enforcement of standardized approaches and thresholds under Basel IV might lead to an oversimplification of the capital calculation, banks want to make sure that they have an internal (Pillar 2) model that mirrors their capital reality more closely. This is where EC modeling can add value.

Another reason EC is back is that, for standalone risk types (particularly credit risk), more granular approaches than the Vasicek model are needed. Suppose one bank has an SME portfolio that is very much concentrated in sectors heavily affected by the pandemic and subsequent lockdown, whereas another bank is well-diversified across sectors but has the same individual exposures. Under such a scenario, the Vasicek formula is much too simple, and it would be very clear that EC-driven systematic drivers are needed to set up a proper statistical loss curve.

IFRS 9, an international accounting standard for expected credit loss modeling, has added momentum to EC's rebirth. Under IFRS 9, risk exposures are represented by cash flows that are subject to macro-economic variables. This aligns very closely with a credit risk EC system, which models the financial health of each obligor as a mix of systematic and idiosyncratic factors.

IFRS 9 data can be leveraged for EC credit risk calculations, so that it addresses the Pillar 2 requirement to calculate credit concentration risk. Indeed, it is not far-fetched to imagine both IFRS 9 expected credit loss and EC credit risk modeling to be two different outputs of the same underlying calculation system.

Although there are valid reasons for the rebirth of EC, calculating EC across different risk types remains a formidable exercise. We still believe that some risk is washed away when combining credit risk with operational risk, but nobody really knows whether this amount is, say, 10% or 20%.

The coefficients that are needed to set up the calculation for inter-risk diversifications are not observable, and very difficult to establish. What's more, as demonstrated by the increase we've seen in operational and credit risks in 2020, COVID-19 surely does not support much diversification.

Future Developments

Whereas EC will probably never function as the sole indicator for a bank's capital requirements, it can assist with the allocation of internal risk budgets, and is an obvious candidate for internal steering on risk versus reward. EC, moreover, can be helpful in providing the correct incentives for building up a credit risk portfolio that diversifies well with the rest of a bank's portfolio.

While the world has changed significantly since 2008, EC is still associated with optimizing return on capital and maximizing shareholder value. Going forward, though, the question is whether this metric will be able to address the key needs of a broader group of stakeholders. For example, will it be able to calculate sustainability risk in the future?

The integration of EC with IFRS 9 calculations and other risk drivers is expected. However, questions still remain about how useful EC is, and will be, in helping firms address extreme tail risk (“1 in 2,000”) events.

Dr. Marco Folpmers (FRM) is a partner for Financial Risk Management at Deloitte Netherlands. He is also a professor of financial risk management at Tilburg University/TIAS.

•Bylaws •Code of Conduct •Privacy Notice •Terms of Use © 2024 Global Association of Risk Professionals